Now it is official: if the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) pursues recognition of the Palestinian people’s claim to statehood in the United Nations this month, financial sanctions will follow. Such a response can be expected not only from Israel, which channels around one billion dollars of Palestinian public revenue to the Palestinian Authority (PA) per annum, but also from major donors whose collective aid has averaged around 1.5 billion dollars in recent years.

Unfortunately, we have been here before and the history of a century of settler colonialism tells us that the economic damage such a move will inflict is considerable. The resilience of a battered people, dispersed between occupation and exile, will be again put to the test as a risky diplomatic strategy unfolds amidst considerable international controversy and internal dissent and skepticism.

Proponents, mainly PLO officials and some scholars, argue that recognition of statehood at the UN is a natural, inevitable outcome of a struggle to end occupation and exercise self-determination; there is no turning back now, indeed no alternative. Detractors include pro-Israeli voices that are hostile to Palestinian rights in any form; for them, the only effective response is one that squeezes the Palestinians, especially financially.

Meanwhile a wide swath of Palestinian activists considers the statehood initiative problematic from legal and representational angles, because of its primary focus on statehood rather than the panoply of denied Palestinian rights. For them the bid for state-recognition is better abandoned or possibly reformulated, as it might lead to either an even more complex situation or hollow diplomatic victory.

Two major encounters are on the horizon. The first, and of greater significance, is how the PLO will address concerns expressed within a national movement fractured along factional, geographic and, increasingly, generational lines. In the second, the PLO and its allies at the UN are confronted with efforts to derail or defuse this initiative. Paradoxically, both of these dynamics are pushing the PLO in the same direction, strengthening its resolve to pursue its strategy come what may. Battle lines are already being drawn, and it is difficult for advocates of any position to escape being perceived as serving one or the other agenda.

If the Palestinians succeed in closing ranks behind the statehood strategy, something that is not apparently imminent, there are ready alternatives to violent resistance. New strategies should aim to strengthen Palestinian economic steadfastness (sumud) and development in a context of national reconciliation, confronting occupation and establishing Palestinian sovereignty, incrementally if need be.

***

If financial sanctions do take hold, this would not be the first time that the reigning powers have deployed them in the century-old struggle over territory and resources between Palestinian Arabs and Zionist (then Israeli) Jews. An eye to history is essential for understanding this conflict’s dynamics as they unfold today. From the British Mandatory authorities’ response to the earliest Palestinian anti-colonial uprising in the 1930s, to military rule over Palestinian Arab minority citizens in Israel from 1948-1966, to annexation of eastern Jerusalem in 1967, to the civil administration of the Israeli military government in the occupied territory, each era had its instruments and purposes.

Nor would it be the first time that finance has impinged on PLO strategies. Beginning with the aftermath of the 1982 Lebanon War, a battered, exiled and isolated PLO had to operate on a tight budget and struggle to maintain its relevance. After 1988, during the first Palestinian intifada, economic sanctions were deployed by Israel throughout the occupied territory to counter popular protests and the PLO’s resurgence. Following the first Gulf War, Arab aid was halted for many years, adding pressure on a reluctant PLO to acquiesce to the terms of the Oslo Accords.

Needless to say, for any national liberation movement, especially one with a major part of its constituency in exile, the support of allied states significantly affects its room for maneuver. This has not been any less the case for the PLO. And when, after the establishment of the PA in 1994, the primary source of funding shifted from external to local revenues largely under Israeli control, this dynamic became even more critical.

Soon after the second intifada erupted in September 2000, Israel withheld import taxes it collected on behalf of the PA, helping to promote a ‘reformed’ PLO which foreswore armed resistance by 2005 and returned to negotiations soon after. And then again, in the wake of the 2006 PA legislative elections, Israeli revenue clearance to the PA was halted, along with direct donor aid. It was only with the Fatah-Hamas schism between the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 2007 that Israeli clearance of revenues was resumed and aid channeled to support the PA budget through consolidated accounts in Ramallah under Prime Minister Salam Fayyad.

By 2010, the PA payroll had become aid and clearance dependent to an extent that interruption of these flows implies a collapse of the PA similar to that experienced in 2002-2004. It is ironic that the fate of the PA, the principal institutional manifestation within Palestine of the PLO is today dependent on uninterrupted flow of ‘conditional aid’ for its very existence.

From this perspective, the real economic miracle of the post-2005 Palestinian regime is not the middle-class urban boom epitomized by Ramallah, much less the institutional achievements of the PA program of the past two years. Rather, what is impressive is that the Palestinian people, at least half of whom live in poverty, continue to resist settlement, occupation, fragmentation and deprivation. The resilience and ingenuity of this core human resource and social capital spread throughout Palestine and beyond should be the lynchpin of a new Palestinian strategy to confront economic and financial sanctions under all and any conditions.

[Striking PA employees. Image from AFP.]

[Pay-day. Image from AFP.]

***

Since the collapse of Palestinian-Israeli negotiations last year, pundits, politicians and the Palestinian public have been debating with increasing intensity the pros and cons of ‘going to the United Nations’ this September. Confusion remains rife as to the exact strategy and purpose of such an initiative, or what shape going to the UN will take after 23 September when PLO Chairman Abbas is due to address the General Assembly). A range of options has been suggested, based on different assumptions as to exactly where in the UN the PLO is going (Security Council and/or General Assembly) - and with what outcomes in mind (full member or observer State).

But process can easily trump everything in the UN. Small words here and there, choosing this or that rule of procedure, and making this or that alliance, counts for everything in such a diplomatic push fraught with risks. By simply depositing an application for admission as the 194th State Member, the PLO will have ‘gone to the UN’ and could conceivably leave it pending. An alternative route could go further, namely requesting the General Assembly to “recognize” the state of Palestine on the 1967 borders and accord it the status of Observer State (instead of the PLO’s status since 1974 as Observer National Liberation Movement). However, following the law of unintended consequences, drawn out negotiations coupled with the looming threat of sanctions, could produce a resolution with new language. This would have to be reconciled with the historic consensus positions set forth in key UN resolutions since 1947, which constitute the legal framework for any resolution of the Question of Palestine, an item on its agenda for sixty-five years.

Regardless of the procedural and legal pitfalls, for those states opposed to this initiative, the Palestinians are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. The Palestinian national liberation movement has tried everything: a failed armed struggle for forty-five years; two popular uprisings ignited by deprived youth; two decades of fruitless bilateral negotiations; and, in the PA, a proto-state – a security and service-delivery apparatus devoid of sovereign powers and split between two (already separated) regions.

Now, friends and foes alike are telling the PLO that recourse to the legal framework of the UN, the international custodian of the Palestine Question, may have dire economic and political consequences. And if the PLO does not go to the UN, then it will be held accountable one way or the other. The vocal Palestinian “patriotic” public opinion concerned about the initiative, either in principle or in its formulation, should not be underestimated.

The PLO is facing diplomatic pressure because this initiative is perceived as an attempt to re-define an otherwise moribund bilateral ‘peace process’ within a broader multilateral setting. But General Assembly Resolutions 181 and 194, and Security Council Resolutions 242 (1967), 338 (1973) and 1397 (2002) are not just historical footnotes to today’s conflicts. The UN has been the indispensable venue for setting the basic parameters of a just (and therefore durable) resolution to the Question of Palestine. And Palestine is ingrained in the UN agenda not out of inertia but rather owing to its inherent staying power as a festering heritage of twentieth century colonialism. So bringing it back to the UN could indeed be an important first step in applying the lessons learned from 20 years of failed diplomacy.

Efforts can be expected to try to neutralize this initiative, through creative language and generic formulations of goals, desired actions and outcomes. Other potential traps could be endorsement of yet another interim period, the most recent version of which was the PA Homestretch to Freedom of 2009-2011. In such an eventuality, major economic consequences and a popular backlash against the status quo are well within the realm of the possible, given the history of failed Palestinian expectations.

From the PLO’s vantage point, retreat is not an option. And while vibrant internal debate is a healthy sign of a pluralist political culture, it has yet to influence existing plans. For better or worse, a Palestinian initiative is imminent, and millions of Palestinians and others will be watching closely to see how it unfolds.

For all intents and purposes, the Question of Palestine is going back to the UN this September. And when the financial heat is likely turned up, the Palestinian economic situation basically goes south. Hence, my concern as a development economist is to examine what I can claim, with some confidence, to know something about.

***

Little of the flood of political, legal and media analysis of this story has touched on what might happen – including economically – after the dust of the diplomatic battle has settled. What impact might the face-off of the coming months and its diplomatic fallout have on the livelihoods of Palestinians living under Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza Strip? Will life just go on under the economic union between six million Israeli Jews and five million Palestinian Arabs, living under the same fiscal, monetary, trade and security regime (geared to the interests of the Israeli Jewish economy) since 1967? And how might this affect the fate of over one million Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel and millions of Palestine refugees?

For most donors, the PLO initiative might not warrant reconsideration of their 1.5 billion dollar annual aid commitments, which comprises around a fifth of Palestinian national income. But for Israel, which clears to the PA, or captures through external trade flows, an even greater proportion of Palestinian public revenue, the Palestinian economy has always been a captive market. For the PLO and PA, which has no contingencies or savings for a rainy day to deal with what might happen after September, any reduction in budget support is a matter of immediate and vital concern. Its 170,000 public sector employees constitute a major source of grievance if the government can no longer honor its obligations. The fractured Palestinian economy is vulnerable to yet another shock to its enfeebled structure, which renders its viability a moot point. This is despite a much-vaunted recent recovery that included “Building the Institutions of the State” and a decade of Washington Consensus-style reform and ‘good governance’.

One way or the other after September, the Palestinian economy will pay a price.

Whatever the outcome, insistence on recognition of the Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza implies, for the PLO, living up to that claim through starting to act as a sovereign entity where possible. This is not only a matter of protocol and diplomatic relations, but equally should be manifested in a major shift on the ground, differentially in the West Bank than in Gaza Strip. In 1988 we witnessed the PLO’s Declaration of Independence of the State of Palestine, and in 2011 we might yet see belated international recognition. Yet after all that has been learned (or not), might the current juncture provide a chance to actually begin establishing that state in 2012?

In Gaza for example, the occupying power’s control over economic policy (fiscal, trade, industrial, investment, banking) is already less than in the West Bank, a crack in the matrix of economic control that implies a policy space begging to be expanded. And if an overdue Palestinian reconciliation enabled a return of the PLO to Gaza, enormous economic implications would ensue from re-establishing the Palestinian financial center of gravity in Gaza where it was based from 1994-2001. Though this would call for new Palestinian power-sharing arrangements, there should be no doubt that the Palestinian economy will pay dearly without national unity and sustained efforts to combat geographic fragmentation. The risk of ending up with little more than Bantustans, ruled through differential levels of occupation and local authorities, cannot be overemphasized in considering any statehood strategy. The economic dimensions of such an outcome would be no less devastating than the process in South Africa where settler colonialism morphed into apartheid.

In response to expected sanctions, the putative state of Palestine, headquartered perhaps in the beachhead afforded by Gaza, would need to plan for alternative arrangements for public finances and external trade. It would have to move away from the failed neoliberal prescriptions of recent PA economic policy. The Gaza Strip has a potentially open border with Egypt, and since 2007 Israel has effectively abandoned application of the customs union which remains in effect in the West Bank. In Gaza at least, the direct financial lever of Israeli control of tax revenues need no longer be a sword held over the Palestinian public purse.

Even with continued Israeli control of the Palestinian coast and airspace, Gaza’s trade with the rest of the world could be re-routed to transit through Egypt and Jordan. Arab financial aid for reconstruction and development could also flow freely and employ a capable but forcibly idled workforce. New proactive monetary arrangements could be considered consistent with a national development vision. Aid could be focused on the most pressing social welfare, infrastructure and productive sector rehabilitation needs.

A resurgent Gaza, cushioned by some degree of economic predictability in the West Bank, could serve as the nucleus of a developmental state of Palestine, economically integrated with its Arab hinterland and enjoying a tentative degree of real sovereignty. While a state of Palestine might be able to carve out some independent security, political and economic policy space in the Gaza Strip, the fate of the occupied West Bank cannot be dealt with in isolation, as colonial policy might have it.

It would be wholly consistent with the principle of going to the UN that the administration of Palestinian public finances, security and other services currently delivered by the PA in the West Bank territory still controlled by Israel, be assumed by an international trusteeship, in close consultation with the PLO, until it was freed of occupation. In such an eventuality, the Protocol on Economic Relations in place since 1994 could be administered by the international trustees along with Technical Departments run by current PA staff. The same local authorities and bureaucracy could provide social services and public utilities.

This would constitute a transformed landscape. It is wishful thinking perhaps. Yet this vision allows for peaceful progress towards achieving Palestinian rights while minimizing reversal of Palestinian institutional and diplomatic achievements of the past decades.

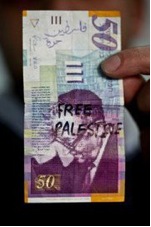

[Palestinian Shekel? Image from aboriginalnewsgroup.blogspot.com]

[Palestine Mandate Currency. Image from vision.net.au/~pwood/oct05.htm]

***

As elsewhere in the region, Palestinian youth are losing trust in the PLO and its ageing leaders. The recent rumblings of a Palestinian social movement indicate that many have also lost respect for the judgment and wisdom of governing elites. Combined with the tensions arising from the growing nonviolent popular struggle against prolonged Israeli occupation, and its latest stage of boycott, disinvestment and sanctions, this makes for a potent brew indeed.

A reformed and accountable PLO, freed of the burden of directly administering the occupied West Bank, would have to be prepared for long-term, peaceful, mass mobilization. It should be inspired by a new model of growth with equity emanating from Gaza and echoing the changes ongoing in the region. Building a Palestinian developmental state calls for more than technical solutions and indeed foresees a societal transformation no less significant than that of the Arab Spring.

If the state-recognition bid at the UN is considered to be such a threat to the “peace process,” then it is time for the international community to offer something new instead of donor-driven economic prosperity within West Bank bubbles. This will require an end to diehard habits of blindly supporting occupation while simultaneously throwing aid at the Palestinians to keep them quiescent – economic peace indeed! Regrettably, the most enduring accomplishment of the peace process launched twenty years ago in Madrid has been expanded Israeli settlement and prolonged occupation. Those opposed to peaceful diplomatic and legal initiatives should offer a meaningful and effective vision for Palestinian freedom and sovereignty that delivers an end to occupation and not yet another road map to nowhere.

Assuming this sea change does not occur, the Palestinian people should be prepared to respond proactively to sanctions through a sustained campaign to achieve self-determination. Its contentious legal and political implications aside, the state-recognition bid at its core is a cry for help from a people who have for too long been wandering through a Kafkaesque landscape of broken promises, fragmented leadership, and seemingly eternal statelessness. The Palestinian national movement has tried everything, and yet has not been able to fulfill its promise of liberating the land and the people, neither for Palestinians living as “citizens” without citizenship under Israeli rule nor for those refugees awaiting return from their diasporas.

So let the process of national liberation resume, and may a thousand Palestinian flowers bloom, maybe even into a Palestinian Spring.

[Click here for an Arabic translation of this article.]